Charleston, South Carolina – The three restaurateurs chosen as the inaugural beneficiaries of a credit card company’s new $5 million initiative to support Black-owned restaurants amid the coronavirus pandemic have several attributes in common: All three of them have Southern roots, intensely loyal fans and a business partner who’s a white man.

According to a spokesman for Discover, since Back in the Day Bakery (Savannah), Post Office Pies (Birmingham, Ala.) and Rodney Scott BBQ (Charleston) were selected for the promotional stage of the #EatItForward sweepstakes, they weren’t obligated to comply with contest rules in order to receive $25,000 apiece. But Derek Cuculich says the company’s vetting process showed the featured restaurants are 50 percent or more Black-owned, satisfying program requirements.

Still, the ownership arrangements mean that at least a portion of the money awarded “to help effect positive change” will not necessarily remain in Black hands.

In the case of Back in the Day, baker Cheryl Day’s co-owner is also her husband, so their professional and personal interests are presumably intertwined. But chefs Rodney Scott and John Hall teamed up with successful hospitality professionals to open their restaurants.

Nick Pihakis, Scott’s partner, had already turned Jim ’N Nick’s Bar-B-Q into a multi-state chain before Rodney Scott BBQ opened in 2017, while Hall’s partner, Brandon Cain, was running Saw’s BBQ when they debuted Post Office Pies in 2014.

Scott and Hall both declined to comment for this story.

Advocates for Black-owned businesses stress there is nothing untoward about financial alliances crossing racial lines.

As Marilyn Hemingway, CEO and president of the Gullah Geechee Chamber of Commerce, puts it, “If your intention is to just put a Black face on it, that’s not equity; that’s cultural appropriation. But if it’s your intention to be an investor, now we’re talking. We are not against good business.”

Hemingway continues, “It’s a totally different situation for a Black man to walk into a bank than for a white man to walk in bank,” so an interracial partnership could help lower a Black entrepreneur’s most significant start-up hurdle.

Offsetting the well-documented lack of access to capital, which has led to African Americans having the nation’s lowest rate of business ownership, counts as good business in Hemingway’s book.

Yet as white consumers show more outward interest in “Black-owned businesses,” the Discover program provides an opportunity to explore precisely what’s meant by the phrase beyond the federal government’s definition of a 51 percent stake, as well as how people and corporations can meaningfully support them.

“There are going to be Black-owned restaurants that don’t get tagged in this contest because they don’t have that feel as ‘Black-owned’ because of the bias we have,” says community activist KJ Kearney, who during the pandemic created Black Food Fridays to shift dining dollars to Black-owned restaurants, which were disproportionately devastated by coronavirus closures.

Under the terms of Discover’s contest, anyone can nominate a Black-owned restaurant for the $25,000 cash prize by tagging it on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter between now and October. Winners will be randomly selected in a weekly drawing, including all the restaurants which have been nominated up to that point.

Initially, the contest website instructed participants, “Even if you’re not sure the restaurant is 50 percent or more black owned, go ahead and nominate them.”

Kearney worries those best guesses about ownership are likely to ride on people’s preconceived notions about Black-owned restaurants and their proprietors.

“We think they’re in the kitchen and running the cash register and cleaning the toilets,” he says. “And definitely, the majority of these places are non-employee or have very few employees. Mesu and Bourbon & Bubbles aren’t in their mind because they’re like, ‘I don’t see a Black person scrubbing the toilets.’ ”

Kearney says he relishes the chance to point out that both Upper King Street restaurants are owned by Lamar Bonaparte.

“I do enjoy those moments,” he says. “When you can’t physically see the imprint of that Black person, I think of it as a good thing. It means this person is doing well. I think that’s a beautiful thing.”

Even better from Kearney’s vantage point is the menu at Mesu, which features grilled mushroom tacos and tuna rolls. “I love that Black-owned restaurants are trying to step out of the traditional soul food cuisine,” he says. “We’re used to white people exploring the culinary landscape. We’re not used to a Black dude doing it.”

At the Montgomery, Ala., restaurant where he worked, Jason McCall’s father cooked Cornish hens and chicken cordon bleu. No matter how well he prepared them, though, credit went to his employer.

“If the food tasted good, the hotel’s name was celebrated,” says McCall, assistant professor of writing at the University of North Alabama. “It wasn’t his name.”

After McCall moved to Florence for his faculty appointment, he and his father started discussing the city’s food and restaurants. Although McCall and his father rarely talk about race, in part because they’re forever dealing with the subject as Black men in Alabama, McCall’s father surprised him by asking of a place he mentioned, “Are they Black owned?”

McCall wrote a poem by that title about the exchange. It appears in the current issue of Southern Foodways Alliance’s Gravy. Its second stanza begins, “Are they black owned? He only cares/that the plates I can afford because of my new job/help put food on another black family’s plate.”

“Even if these chefs have white co-owners, being a co-owner is such a cosmic step forward,” McCall says. “Even if they own a small piece of the pie, that piece was completely locked away for people who just worked. (My father) was never going to own any of it.”

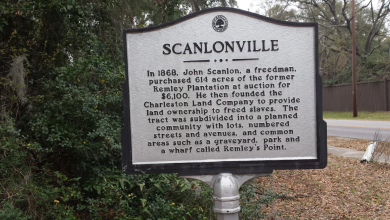

And in the South, McCall says, ownership has added resonance.

“Because of the tradition of slavery, ownership carries a certain weight,” he says. “There is that sense that the Black experience starts as property, and then if you own a business, you become the property owner.”

As much as McCall would have liked to see that for his father, he acknowledges that changing roles doesn’t change the stage on which they’re played.

“With Black ownership, there’s these multiple streams of pride, but also the fact that it comes in a system built on exploiting Black people,” he says. “The American banking system is brutal. So what does it mean to have a seat at the table if the table is broken? What does it mean to own the house if the house is on fire?”

In other words, McCall is concerned about the price of propping up capitalism, even if Discover is willing to pay five figures apiece to the black restaurateurs chosen through its current campaign.

“If you dig through the history of Discover, you’ll probably find it would take a lot more money to make up for the money a company like Discover made off black communities,” he says.

Indeed, the scope of economic inequality is so vast that Kearney is skeptical any program focused exclusively on the restaurant sector can shrink it, especially if it doesn’t prompt consumers to be purposeful in their spending on a regular basis.

Recently, Kearney noticed that participation in Black Food Fridays was starting to flag slightly. It led him to wonder if some early participants found the hashtag more appealing than the prospect of making “the mental switch to be aware that black businesses exist and have financial heartaches.”

Such an awareness could result in a white church placing a standing order for altar flowers with a Black florist, as he’s heard historian Millicent Brown suggest. “That would be life changing,” he says.

Systematic change, Kearney emphasizes, entails more than getting a burger. In his view, that’s true regardless of what percentage of the sandwich’s sale price ends up in a Black business owner’s pocket.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.